สีผึ้งจันทร์เพ็ญ (ปี2565), “พระราชสิริวัชรรังษี” หลวงพ่อท่านเจ้าคุณชำนาญ อุตฺตมปญฺโญ, วัดชินวรารามวรวิหาร, จ.ปทุมธานี

ของแรงตำรับมอญ "ดึงจิต ขยี้ใจ" สีผึ้งของหลวงพ่อชำนาญ เป็นที่รู้กันว่าเป็นของแรงทางเมตตาหาตัวจับยาก ประสบการณ์สูงส่ง

สีผึ้งรุ่นเก่าๆที่ท่านได้สร้างไว้ คนเอาไปใช้ก็มีประสบการณ์ต่างๆมาเล่าสู่กันฟัง อย่างเช่นว่า มีสาวหล่อนำไปใช้ ก็ใช้ดีขนาดว่าใช้ตลับเดียวมีเพื่อนหญิงเป็นร้อยใช้จนแห้งตลับจึงเลิกซ่า, มีคนจะเดินมาชกหนุ่มคนนึง หนุ่มคนนั้นก็รีบเอาสีผึ้งแกล้งจับแขนคนที่จะเดินมาชก อยู่ๆเขายกมือไหว้เฉยๆ บอกว่าเหมือนคนเคยรู้จัก, พ่อค้าแม่ค้าที่แผงผลไม้ในตลาดไท เอาสีผึ้งไปแต้มหน้าร้าน ก็ปรากฏว่าขายดิบขายดีจนหาผลไม้มาลงแผงไม่ทัน หรือแม้แต่หมอเขมรที่สุรินทร์ ก็ยังต้องเอาสีผึ้งหลวงพ่อชำนาญไปผสมทำเครื่องรางเลยทีเดียว

สำหรับมวลสารที่หลวงพ่อชำนาญท่านนำมาสีผึ้งนั้น ล้วนแล้วแต่เป็นของดีที่มีอานุภาพในตัว อาทิเช่น เทียนชัยในพิธีพุทธาภิเษกต่างๆที่หลวงพ่อชำนาญท่านได้เก็บสะสมไว้, ว่านมหานิยมอีก 7 ชนิด, ผงอิทธิเจ, ผงนางอกแตก, ผงเนียฮะวา, ผง 12 นักษัตร, และยังมีสีผึ้งชุดเก่าของครูบาอาจารย์ต่างๆอีกมากมายนับไม่ถ้วน

มวลสารทั้งหมดที่กล่าวมานี้ถูกนำมาเคี่ยวรวมกัน โดยไฟที่ใช้ในการหุงจะต้องนำไม้มงคลมาเป็นฟืน อาทิเช่น ชัยพฤกษ์ ราชพฤกษ์ มะยม มะรุม รัก กาหลง ขนุน ตำลึง เป็นต้น หลังจากนั้นจึงนำไปหุงซ้ำตามฤกษ์มงคล แล้วนำไปตากแสงอาทิตย์ 7 วัน ตากแสงจันทร์ 7 วัน ตากฝน 7 วัน ตากฟ้าอีก 7 วัน จนกว่าหลวงพ่อชำนาญท่านจะเห็นควรว่าสีผึ้งมีพุทธคุณเต็มเปี่ยม จึงจะนำออกให้ผู้ศรัทธาได้ร่วมทำบุญกัน

สำหรับสีผึ้งจันทร์เพ็ญของหลวงพ่อชำนาญนี้ ท่านได้ตั้งชื่อตามฤกษ์ ตามพิธีสำคัญที่ท่านใช้ในการเสกสีผึ้ง คือเสกในฤกษ์ดิถีมงคลที่เรียกว่า "จันทร์เพ็ญ" เพื่อรับพลังจันทราเมื่อจันทร์เพ็ญส่องสว่างเต็มดวง ซึ่งถือเป็นฤกษ์แห่งความอุดมสมบูรณ์ด้วยพลังอำนาจอันลึกลับของพระจันทร์ เป็นที่สุดแห่งห้วงเวลามหาเสน่ห์ “ฤกษ์ดีวันแรง” โบราณจารย์ทุกยุคสมัยนิยมปลุกเสกวัตถุมงคลหรือประกอบพิธีกรรมมงคล ที่เกี่ยวกับเมตตามหานิยมโชคลาภในฤกษ์นี้ เพราะอำนาจแห่งแสงจันทราจะเสริมความเข้มขลังศักดิ์สิทธิ์ให้แก่วัตถุหรือพิธีนั้นๆเป็นเท่าทวีคูณ

การบูชาและรับพลังจากแสงจันทร์ตามตำราโหราศาสตร์ด้วยเชื่อว่าอิทธิพลจากพลังอำนาจพระจันทร์ ในแต่ละช่วงนั้น ย่อมที่จะส่งผลต่อมนุษย์บนโลกในแง่ต่างๆ พลังของพระจันทร์มักใช้เกี่ยวเนื่องกับเรื่องราวทางจิตวิญญาณ ศาตร์เวทย์ลึกลับที่เสริมอำนาจ วาสนา พลิกชะตาชีวิต โดยศาสตร์เวทย์โบราณพบว่าพลังอำนาจของพระจันทร์จะทรงอำนาจทางเสน่ห์และเมตตา มหานิยมยิ่งนัก พลังของพระจันทร์จะมีผลโดยตรงต่อชะตาชีวิตของมนุษย์บนโลกและการถือกำเนิดขึ้นของมนุษย์บนโลก ล้วนถูกกำหนดจากตำแหน่งของพระจันทร์และดวงดาวบนท้องฟ้า

ด้วยการประกอบพิธีกรรมอย่างถูกต้องและพลังอำนาจแห่งพระจันทร์ผนวกกับมวลสารอาถรรพ์ที่มีคุณในตัว จะทำให้มวลสาร วัตถุมงคลนั้นๆเปี่ยมไปด้วยพลังที่จะเสริมสง่าราศี เสน่ห์เมตตาสูงส่ง ผู้ใหญ่เอ็นดู ช่วยเหลือ หันหน้าไปในทิศใดก็ไม่มีผู้รังเกียจ เป็นที่รักใครของทั้งมนุษย์และเทวดา แก่ผู้ครอบครอง นอกจากนั้นยังทำให้เกิดโชคลาภวาสนาต่างๆประเสริฐนัก

Full Moon Wax (Year 2022) by "Phra Rajsiri Wachararangsi" Luang Por Than Chao Khun Chamnan Uttamapanyo, Abbot of Wat Chinwararam Worawihan (Royal Monastery), Pathum Thani Province.

A powerful charm from the ancient Mon-Raman lineage, a true "Heart & Soul Puller". The magic wax (See Phueng) of Luang Por Chamnan is widely recognized as one of the most potent sacred balms in the realm of Metta Mahaniyom (loving-kindness and attraction).

With a long and respected legacy, some of his older batches have gained legendary status, bringing extraordinary experiences to those who used them. One famous story tells of a tomboy who used just one cassette of the magic wax, and ended up with over a hundred female friends, completely disarmed by her charm. She only stopped after the wax ran dry. In another account, a man about to be punched by someone used the wax subtly by grabbing the attacker's arm. Miraculously, the attacker stopped and greeted him with a respectful action, saying it felt like they'd met before. Fruit vendors at the Talad Thai market have used it by dabbing some on their stalls, and suddenly experienced such booming sales that they couldn’t restock fast enough. Even a Khmer ritual healer in Surin province was reported to have sought out Luang Por Chamnan’s wax to blend into his own spiritual amulets, a true testament to its revered power.

The sacred materials used by Luang Por Chamnan in the making of his magic wax are all powerful in their own right, each possessing spiritual potency and deep esoteric value. Among them are: Ceremonial Victory Candles (Thian Chai) from various Buddha blessing ceremonies (phuttha phisek) in which Luang Por Chamnan himself participated and carefully collected over time, Seven types of “Maha Niyom” (great attraction) sacred herbs, Phong Itthije, Phong Nang Ok Taek (powder of the “heartbroken lady”, a charm of irresistible allure), Phong Nia Hawa (a rare love and charm powder of Mon-Raman origin), Phong 12 Naksat (powder representing the twelve zodiac animals, for destiny and cosmic balance), Along with countless other rare magic waxs and sacred powders from past masters and revered teachers, many of which are now impossible to find. These sacred components were not merely symbolic, they were chosen and preserved with purpose, forming the heart of Luang Por Chamnan’s spiritually-charged magic waxs.

All of these sacred ingredients were carefully simmered together in a ritual process using a fire fueled exclusively by auspicious woods, such as Chaiyaphruek (Cassia fistula), Ratchaphruek, Mayom (Star Gooseberry), Marum (Drumstick tree), Rak (Love tree), Kha-long (entangling vine), Jackfruit, Ivy Gourd, and others. After this initial process, the magic wax was then cooked again under an astrologically auspicious time, in accordance with ancient ritual traditions. Once prepared, the magic wax was subjected to a fourfold elemental blessing: Sun-bathed for 7 days, Moon-bathed for 7 nights, Rain-bathed for 7 days, Sky-exposed for another 7 days. Only when Luang Por Chamnan determined, through his meditative insight, that the magic wax had reached its full spiritual potency would he then allow it to be released to the faithful, as part of a sacred act of merit-making.

The name "Full Moon Wax" (See Phueng Janphen) was given by Luang Por Chamnan in direct reference to the sacred timing of its consecration. This powerful wax was blessed under the auspicious astrological window known as “Janphen”, the moment of the full moon, when the moon shines in its most radiant and complete form. In ancient Thai and Buddhist traditions, this lunar phase is believed to be the peak of mystical lunar power, representing abundance, attraction, sacred energy, and supernatural charm. It is considered a “Great Day of Fortune”. Throughout generations, Thai esoteric masters have favored this exact timing for consecrating sacred objects related to Metta Mahaniyom (loving-kindness, charm), wealth attraction, and ritual potency. It is said that under the light of the moon, symbolic of the full spiritual brightness, any object or ritual performed gains amplified power and sacredness, exponentially magnified by the energy of the moon itself.

In traditional astrological teachings, moon worship and the harnessing of lunar energy are believed to profoundly influence human life. Each phase of the moon is thought to carry distinct energies that can affect individuals on both physical and spiritual levels. The power of the moon is often associated with the mystical arts, spiritual rituals, and esoteric sciences, used to enhance destiny, charisma, personal power, and even reverse misfortune. According to ancient occult wisdom, the moon holds exceptional potency in matters of love, attraction, charm (Metta Mahaniyom), and compassion, making it a central force in many sacred rituals throughout history. The influence of the moon is said to directly affect human fate, with one’s birth and life path shaped by the moon’s position and the arrangement of celestial bodies at the time of their arrival into the world. Thus, rituals performed under lunar alignment are believed to unlock powerful cosmic energies, aligning the soul with universal forces for transformation and spiritual growth.

Through the proper performance of sacred rituals combined with the powerful energy of the moon and the inherent potency of the mystical ingredients, the resulting sacred object or charm becomes infused with profound power. This power enhances the wearer’s prestige, charm, and loving-kindness, attracting the goodwill and support of respected elders and influential people. Wherever the wearer turns, they face no hostility or rejection, instead, they become beloved by both humans and celestial beings alike. Moreover, these blessings bring forth great fortune, luck, and auspicious destiny, enriching the life of the possessor in the most excellent ways.

หลวงพ่อชำนาญท่านได้สร้างสีผึ้ง ตามตำรับของ "หลวงปู่สุรินทร์ เรวโต (พระครูปทุมธรรมานุสิฐ)" อดีตเจ้าอาวาสวัดบางกุฏีทองที่เป็นองค์อาจารย์ของหลวงพ่อ ซึ่งในสมัยที่หลวงปู่สุรินทร์ยังดำรงค์ธาตุขันธุ์อยู่นั้น เวลาหลวงปู่สุรินทร์ท่านทำสีผึ้ง ถึงขนาดต้องทำในมุ้ง เพราะแมลงนกหนูจะมาล้อมกันเต็มไปหมด และพอเสกได้ที่ต้องเกิดฟ้าผ่า สมัยหลวงปู่สุรินทร์ทำแล้วขลังขนาดนี้

โดยสีผึ้งแต่ละรุ่นที่หลวงพ่อชำนาญท่านได้สร้างไว้ ก็ได้เกิดปรากฏการณ์ที่เป็นิมิตหมายมงคลเช่นกัน อาทิเช่น มีพญานกใหญ่มาเกาะที่วัด (พญานกใหญ่เปรียบเหมือนพญาหงส์เท่ากับสีผึ้งท่านเรียกหงส์ได้ พญาหงส์เปรียบเหมือนเทพราชามารับรู้รับทราบ), กระดิ่งที่ห้อยอยู่ที่ปากหงษ์หน้าวัดดัง ๓ วาระ (ดุจพญาหงส์ร้องทัก), นกบินเข้าวัดรอบทิศรอบทาง (เสมือนว่าใครก็อยู่ไม่ได้ ต้องมารุมล้อม) และยังมีเรื่องแปลกๆที่ยากจะอธิบายอีกมากมาย

Luang Por Chamnan crafted his magic wax following the ancient formula of his revered teacher, "Luang Pu Surin Rewato (Phra Khru Pathum Thammanusit)", the former abbot of Wat Bang Kudi Thong, who was Luang Por's mentor. During the time when Luang Pu Surin was still alive, it was said that whenever he made the magic wax, he had to do it inside a mosquito net, not to protect himself, but because insects, birds, and even mice would flock toward him, drawn by the powerful spiritual energy of the ritual. And when the consecration reached its peak, it was common for a lightning strike to occur, as if nature itself acknowledged the sacred force being summoned. Such was the potency of the magic wax when Luang Pu Surin made it, a level of spiritual power that left no doubt of its mystical strength.

Each batch of Luang Por Chamnan’s magic wax has been accompanied by remarkable and auspicious phenomena, signs interpreted by many as spiritual affirmations of the magic wax’s power. For instance, a majestic bird once appeared and perched at the temple. This was no ordinary bird, many saw it as a manifestation of the Celestial Swan (Hongsa), a royal divine being in Thai-Buddhist cosmology. The presence of such a bird was taken as a sign that the magic wax had summoned the Celestial Swan, a symbol of heavenly royalty and divine acknowledgment. On another occasion, the small bell hanging from the mouth of the swan statue at the front of the temple rang three times in three clear tones, interpreted as the call of the Celestial Swan itself. Birds were also seen flying in from all directions, circling the temple, as if drawn by a mysterious force, or as if the magic wax’s power made the temple an irresistible spiritual magnet. Beyond these, there have been numerous other strange and unexplainable events surrounding the making of the magic wax, phenomena that continue to deepen the mystery and sacredness of Luang Por Chamnan’s creation.

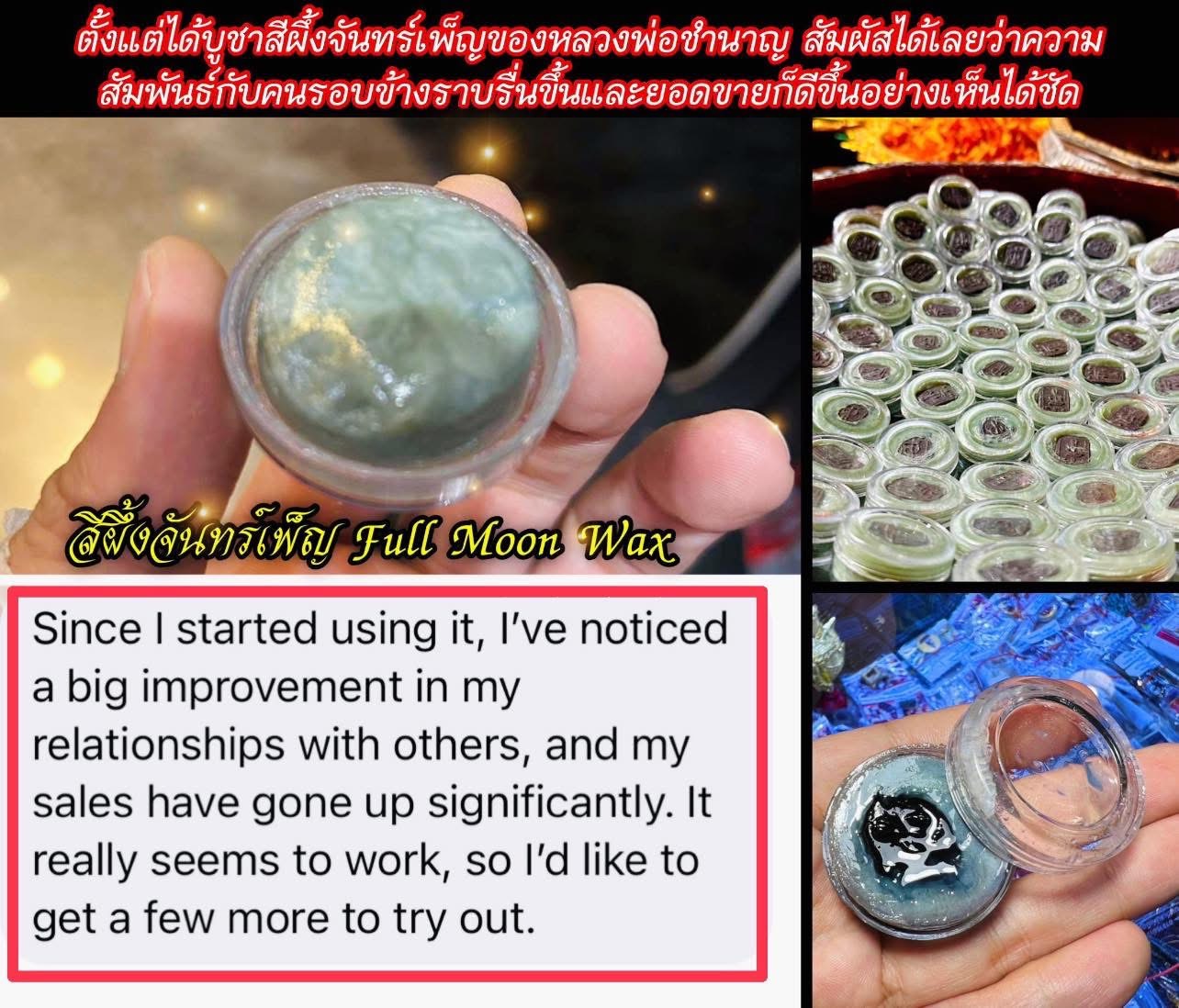

ผู้ศรัทธาชาวต่างชาติท่านนี้ มาตามเก็บบูชาไปอีกหลายตลับ “สีผึ้งจันทร์เพ็ญ” เต็มเปี่ยมด้วยพลังเสน่ห์แห่งพระจันทร์เต็มดวง ใครได้บูชาต่างยืนยันเป็นเสียงเดียวกันว่าใช้ดีจริง

This foreign believer returned to collect more of “Full Moon Wax”, renowned for its mystical charm drawn from the power of the full moon. Everyone who has worshipped it agrees, it’s truly effective.

ตั้งแต่ได้บูชา “สีผึ้งจันทร์เพ็ญ” ของหลวงพ่อชำนาญ สัมผัสได้เลยว่าความสัมพันธ์กับคนรอบข้างราบรื่นขึ้นและยอดขายก็ดีขึ้นอย่างชัดเจน สีผึ้งรุ่นนี้เมตตาแรงจริง ใช้ดีจนผู้ศรัทธาอยากเก็บบูชาเพิ่มอีกค่ะ

Since he started using the “Full Moon Wax (Seephueng Janpen)” by Luang Por Chamnan, he could truly feel that his relationships with people around him became smoother, and his sales noticeably improved. The power of kindness in this wax is so effective that he now wants to get another one.

อีกหนึ่งเสียงความประทับใจจากผู้บูชาสีผึ้งจันทร์เพ็ญ ใช้แล้วดีมีความสุข การค้าก็รุ่งเรือง พอได้บูชาก็ยิ่งรู้สึกศรัทธาในบารมีของหลวงพ่อชำนาญเป็นอย่างมาก

Another heartfelt review from a believer of the Full Moon Wax brings happiness and thriving business. After worshipping, their faith in the sacred power of Luang Por Chamnan.